Dear diary,

We’ve been asked by Chris and Michelle to write a post that summarises 5 things we’ve learned in the fellowship so far. It’s been a great prompt to take stock and summarise the vast amount of learning I’ve done. I dashed off a quick list a few weeks back. Since then, whenever something new pops into my head I’ve added it to the list, and before my eyes that list has grown to 12 things. Um…. not really meeting the brief here am I? 😆

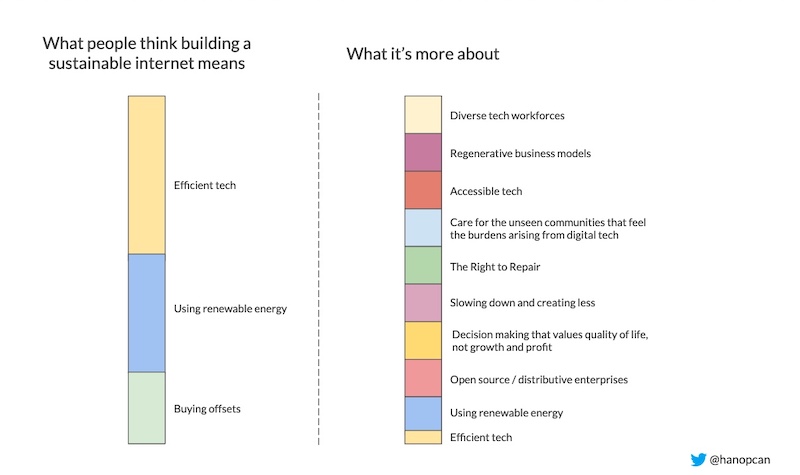

I also recently spotted a popular post on LinkedIn from Adam Bastock, highlighting the difference between what people think climate action involves and the reality. That post was in turn inspired by this post by Sarah Daly, which in turn was inspired by Stefanie Blank’s post.

Anyway, I love the simplicity of a good diagram/mene and I felt inspired to use the same concept to articulate some of the things I’ve learned, and to see if I could rationalise my ever growing list.

My diagram

What you see above is version 2. You can also view this as a higher resolution google slide, and use under a creative commons license.

I shared my first version with the fantastic Climate Action Tech Slack community to see how it resonated and what feedback arose. It generally got a thumbs up from the community, and a few people were kind enough to share a few thoughts with me.

Dave DuVerle suggested that I could be “focussing on the positive outcome from the actions on the right-hand side”. A helpful prompt, and very much the point that was being made in the initial post I saw. My original version was more action orientated than outcome focused, so that got changed.

Laurent Savaete also made a good point, which was that I should make it clear that there’s no agreed definition for what a sustainable internet is, and it would be good to “convey a little bit of doubt and critical thinking that cannot hurt in this shift”. Another good point, and I changed the title on the right to reflect that.

Beyond that I also got some good questions from others in the community who were interested in why I wrote the list I did. Not all of the items might seem obviously relevant to a sustainable internet at first glance.

So, in the spirit of the fellowship, I thought I’d write down some brief notes to convey how I see the points on the right on the diagram as relevant to building a sustainable internet. I think it possible you could write an essay/book for each of these points, so I will endeavor to keep the reasoning short and punchy. Here goes…

Quick explanations of what I put as outcomes and why

Central to my thinking is that the sustainability of any thing encompasses three pillars:

- Social

- Economic

- Environmental

The three are so intertwined that it’s impossible to tell where one starts and the other ends. There are overlaps a plenty. Something that might sound purely environmental, like carbon emissions, most certainly isn’t. It’s deeply connected to social and economic issues.

As such, the outcomes I’ve written down definitely intersect with one another, and are not discreet. Bring on the fuzzy lines.

Diverse tech workforce

Given climate justice and sustainability are intrinsically linked to social issues, I feel this deserves the top spot in the outcomes list. It’s well documented that the tech industry has a diversity problem. I mean diversity in the broadest sense incorporating gender, ethnicity, economic background, sexual orientation, disability, education level, cultural values and so on. The people designing tech and making decisions about it, are not representative of all the types of people using it or affected by it.

I also think it’s fair to say, that those communities affected either directly or indirectly by digital tech, and not necessarily using it, are also not represented among the makers. Those voices are not being heard and their impacts not accounted for strongly enough. They are simply overlooked. And those voices might also be the voices with the deepest connection to the local environment, and the best ones to tell us where we’re getting it wrong.

Imagine such a diverse workforce building a sustainable internet, that it includes people who don’t even use the tech! 🤯 Read more at Design Justice.

Regenerative business models

I see a regenerative business model as one that seeks to create multiple layers of value, rather than solely seeing value as something to extract and stockpile. In today’s terms that’s taking money out of a business for shareholders.

Regenerative business models are also similar to the concept of circular economies, which seek to give back to and restore the living systems of which they are a part. A great example is phone manufacturer FairPhone.

In our digital context, these can be business models that look for win-win outcomes by building a product or service to serve the needs of customers, and at the same time creates additional benefits to wider society and/or the environment. For more see the Doughnut Economics videos on regenerative and distributive design.

A sustainable internet might be made up of organisations that not only connect people, but also actually enrich their lives outside of the internet / screen itself.

Accessible tech

When there’s effort to make tech available to a wider audience, it makes that tech vastly stronger and more resilient, and everyone benefits.

A sustainable internet is going to be one that can endure because it serves the needs of the many and designs for stress cases.

Care for the unseen communities that feel the burdens arising from digital tech

There is a really strong overlap between this and diverse tech workforces, but I think this point is so important it needs to be its own thing. One of the core principles of climate justice is that those who have done the least to cause climate change are the ones who feel the burdens the most. Here we are referring to marginalised communities, for example black and indigenous communities.

You can also argue the same is true of digital tech; those who have contributed the least to its creation, feel the negative impacts the most.

A sustainable internet would be one that takes a holistic, and genuine view of its impacts and actually cares about the people who suffer because it exists. The communities whose land is transformed to house vast data centers, extract rare raw materials or create the energy to power it all for example.

The Right to Repair

This is a principle that says we should be empowered to repair and upgrade the tech we buy, not forced to throw it away when there’s a problem, or when the next best thing hits the market.

Many large tech firms have an explicit strategy called planned obsolescence, which in the words of Repair.eu means “when a manufacturer consciously makes design and manufacturing decisions that result in a limited product life”.

A sustainable internet is one where we can extend the life of the tech we own legally, and without barriers. Phones that last 10 years as a minimum? Yes please, that’s a future I’m up for.

Slowing down and creating less

We need to slow down, and focus. We also need to claim our attention back.

We need to think more, and ask more questions before we create tech stuff that embeds into our society and struggles to be undone. We need to care more about bringing others on the journey with us in anything we create.

This all takes time, and so it should.

A sustainable internet is one that exercises caution. Of course that caution needs to be balanced with innovation that makes the world a better place, but the pace of change in the tech world is reckless. Just because we can, does not mean we should.

Decision making that values quality of life, not growth and profit

For me this point is about wider politics and societal systems. Let’s switch out valuing GDP and profit above all else for valuing life, both the life of humans and the life of others we share this planet with.

I think Doughnut Economics provides a great vision for what this could be. We need a dramatic shift in this area, and we need to see more being done by governments to incentivise making longer-term, sustainable decisions that benefit future generations and not just shareholders today. Also Less is More by Jason Hickel is a good read.

A sustainable internet, and the component parts with it, is therefore something that exists to promote quality of life over profit.

Open source / distributive enterprises

In a code sense, it’s a model that most developers would be very familiar with. It’s the idea of making the software freely available for others to use and actively inviting collaboration and participation in its development. This idea can apply to any type of business product, it doesn’t just need to be software or tech.

Another facet is also thinking about the ownership of any resulting value from the business. Let’s keep it simple and say how the profit is distributed. Is it going to shareholders or to those actively participating in running the business, the workers? For more see the Doughnut Economics videos on regenerative and distributive design.

A sustainable internet is one that distributes the value it creates across as many people as possible.

Using renewable energy

You’ll notice from the diagram this is also one of the points on the left hand side of the diagram. But it’s been massively downgraded to the bottom of the right hand side. Whilst using renewable energy and ditching fossil fuels is certainly important when it comes to creating a sustainable internet, I might argue that if you were taking care of all the other things above it, the impacts of whatever energy you are using would be greatly reduced.

Aside from the massive amount of carbon that burning fossil fuels creates, it’s the economic and political systems that value growth and profit above all else that have allowed fossil fuel companies to dominate us and oppress progress so much. Unless we see a shift in that, we’re likely to end up producing renewable energy in the same damaging and extractive way as we do fossil fuels currently. Some solar farms in India are a case in point.

So a sustainable internet should most definitely run on renewable energy, but how about renewable, ethical energy?

Efficient tech

And lastly, we come to efficient tech. The problem with making tech more efficient is that it doesn’t actually appear to reduce the consumption of resources. In fact, the more efficient it is, the more demand there is and the more that is consumed. Take a look at Jevon’s paradox.

So we can shift all our compute to run at times when the carbon intensity of the grid is lower. Or we can optimise the heck out of our site and deliver it in less than 0.5MB. Lovely. But if we just do that, and we don’t fundamentally address all those other things we’ve totally missed the point.

A sustainable internet is one that does indeed embrace efficient tech, but more importantly it embraces the need to be clear on what we are building tech for, and who we are benefiting and who we are burdening with it.

Licensing

I’ve been asked by a few people since publishing this, if they can use this diagram and ideas in their own work. Of course, you are most welcome to do so, and I would love for others to build upon the ideas. I’ve added a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike license to the diagram, which you can see on this google slide.

Most importantly, if you do build on these ideas, please reach out to me to let me learn from you. That’s what this is all about!

Next steps

I’ve found articulating this really useful and I can already see a bunch of ways to further refine this thinking, and improve it. I’ll be using this diagram in the various talks I give on sustainable technology and I’ll keep taking feedback on board as it comes in.

I don’t think it’s a realistic expectation to arrive at a perfect answer for what a sustainable internet is. It may be easier to describe what it isn’t!