In other posts on this blog, or in Branch Magazine, we’ve gone into some detail about the economics of green energy. We’ve covered how and why the price of energy changes based on the time of day, and in Branch, we’ve explained how the price of green energy has fallen nearly a thousand fold since the late 60’s, compared to the price of fossil fuels largely staying the same.

In this post we provide some background about who tends to pay for a transition to greener, fossil-free energy, and who tends to be credited for it. We cover three sources of funding, and provide examples in the digital sector, to help illustrate how we can get to a fossil free internet by 2030.

We’re in the middle of a transition away from fossil fuels, and this transition involves a major change in how we pay for energy. We’re moving from a system where we make regular payments for fossil fuel to burn, like paying rent to a landlord, and where 40% of all shipping is just moving fossil fuels around world to the right place for when we want to burn them, towards one where once infrastructure has been built and maintenance accounted for, there’s no fuel to pay for, and the energy is effectively free.

But where does this money come from in the first place?

Finding the money for a transition

In the context of energy and decarbonising how we power digital infrastructure, this quote from climate economist Gernot Wagner is helpful:

Ultimately, there are 3 sources of money in the world: ratepayers, taxpayers and shareholders.

Green transition politics is about figuring out who pays.

Gernot Wagner, channeling Julio Freidman

It’s almost always a combination of these groups paying for any green energy project. Once you realise that it’s almost never just one actor doing the work to transition away from fossil fuels, I think it makes it easier to move to different framing than the ones we see playing out in the media, about whether a company really is green or not.

For example, it’s increasingly common to see press releases from companies talking about how they’re going green. If you were to follow the claims at face value, and accept them uncritically, you might come away thinking that’s it’s just a few companies doing all the work to make a transition from fossil fuels happen, and there is literally zero environmental impact from building hundreds of huge new datacentres, nor from running them 24/7.

Not everyone accepts this and counter arguments are varied, but an increasingly common trope rolled out when companies present their planet-saving green energy plans like this is:

they’re using up all the green energy, so there’s none left for us – this doesn’t help at all!

Below is one example of the kind of headline you might see:

Neither of these framings is all that helpful, nor that accurate.

Another way to talk about getting off fossil fuels

Regardless of where you stand on discussions about degrowth, the science is overwhelmingly clear that we need to move away from burning fossil fuels to power our world.

At the same time we’re so invested in fossil fuels that it’s unrealistic to think that we can simply turn off fossil fuel supply without working to replace at least some of the energy people have been reliant on for things like sanitation, heating and so on.

So, if we can accept that there is a need for a transition away from powering our society on dangerous fossils fuels no matter what, and that no one is green until we all are green, then maybe we can make space for a conversation about how the costs, the rewards, and the recognition are distributed instead.

The risk of not addressing this is a mounting opposition to the kinds of projects that would displace fossil fuel usage for generating energy. This is fossil fuel use that right now pollutes our air, and shortens millions of lives needlessly.

Many of the concerns being raised are valid, and this mounting opposition to a transition means it’ll either go more slowly, or in some cases grind to a halt. When it comes to climate, speed is justice, so in the context of our work, instead of talking about a sustainable internet, we think it’s important to talk about just and sustainable internet. To do that, you need to be able to talk about power, not just energy.

Ratepayers, taxpayers and shareholders

So back to the original topic – if there are only ever three sources of money for a transition – ratepayers, taxpayers and shareholders, it’s worth explaining who these groups are, and give some examples in the digital world.

Rate payers – people who pay monthly electricity bills, like you and me.

In the energy sector, rate payer is the industry jargon for someone who pays regular bills, usually at a rate based on how much energy they use each month or each week.

While you totally can buy a green energy tariff in many places (and doing so is a often a good thing!), even if you’re paying for electricity on a bog standard rate, the chances are you’re already spending some money to help finance green energy, because a part of price of each unit of power is dedicated to schemes to pay for the expansion of greener energy.

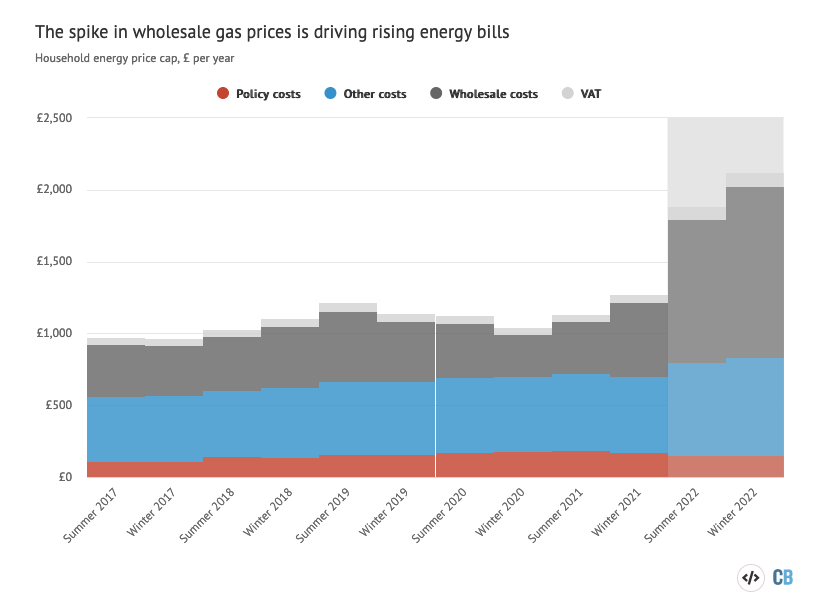

In the UK for example there is a surcharge already built to all our bills automatically – it’s the red section on the bills below and it’s stayed pretty flat over the last year, even as the cost of natural gas has skyrocketed.

In Germany you see a similar situation. Without this surcharge, we likely never would have seen the cost of green energy fall, over the last 20 years in particular, to the point where it is now.

In the United States, it’s a similar arrangement – in many states power companies are regulated in an arrangement called a natural monopoly, that grants them guaranteed profits, as long as they meet the standards set by a regulator.

What’s in these standards varies from state to state but in some places, like California and New York these standards include things like build out this much green energy by year X.

When this happens, the cost of green energy is rolled into the cost of the bills that everyone pays. Anyone who pays for electricity ends up paying for this shift.

In this case, notions of consumer choice or even rewarding companies for being good corporate citizens don’t make as much sense as they would in states where you can choose your provider – it’s not really down to the company to decide to invest in green energy – it’s a condition of being allowed to operate at all.

This also means that if you pay for electricity as an individual, a lot of the time, you’re already doing your part to make a shift happen. Good work, you.

In fact, in some cases, you’re actually doing more work than most companies, because industry players often lobby to be exempted from paying for these parts of energy bills. This is what has happened in Germany, and large parts of the United States – on a per unit basis, you pay more for your electricity than industry players do, because you pay this renewable energy surcharge, but they don’t.

The argument here is that because they use more energy, they should pay a lower rate, and if you lived in the Netherlands near that datacentre in the story above, this might be the argument used to justify selling electricity to companies like Facebook lower rates than you might pay.

The thing is, when a large organisation gets cut-price rates for power, the shortfall in revenue has to come from somewhere, and a lot of the time it’s the ratepayers picking up the bill.

At times like this, rather than getting caught in an argument about who’s using all the green energy when the energy is physically fed into the same grid anyway, you might ask yourself if it’s better to ask if the costs and rewards of a transition are being shared equitably instead. On our Greenweb Fellowship programme, Hannah Smith has a great post on this topic.

Tax payers – payments from the government, or tax breaks to encourage the use of renewables.

As you’d imagine, one of the problems with shifting costs onto ratepayers like this, is that while it’s easier to hide the costs, and politically easier to do, it’s not very equitable. The poorer you are, the more you end up paying as a share of all the money you earn each year.

Faced with this, another way to pay for a shift to renewable energy is to do it from money raised through taxation. Generally speaking, this approach is less regressive, because the money is coming from groups like higher rate tax payers are are already pretty well off, and where spending on energy is a much lower share of their revenue and wealth overall.

When it comes to the internet world, it’s also common to see subsidies and tax breaks being dished out to companies to encourage spending on renewables, often to power datacentres, with the thinking here being that the extra economic activity will create jobs, or tax revenue further down the line.

This has translated to a windfall for big tech companies, and this interview with the CEO of one of the companies developing these energy projects is instructive. When Google signs a 15 year supply deal for a datacentre to have a matching wind farm or solar array, it’s definitely committing a bunch of money up front, but a lot of the time, it’s also getting help from tax payers in the form of subsidies to pay for it.

This means that the price the company might pay for each megawatt hour of power ends up being lower than other competing internet companies. Where most companies might pay 40-50 dollars per megawatt hour for their power to run their datacentres, often on a regular fossil-heavy fuel mix, large companies like Google might pay between 20 and 30 dollars per megawatt hour instead, because they’ve locked in a lower rate over a 15 year period.

These kinds of deals have led to large tech companies being hailed as the largest corporate investors in renewable energy globally of late, and they definitely are playing a valuable role as anchor customers for all kinds of necessary new forms of energy for a fossil-free internet.

But pretending it’s just that one company doing all the work, and paying for it all is silly – this helps green the internet, but it also means that tax payers end up subsidising trillion dollar corporations.

When the same companies have become known for running elaborate schemes to avoid paying their fair share of tax, and when they lobby to dismantle schemes to provide others similar support for transition that they have been benefiting from, you might ask if in the long term if there are other ways to use taxpayer money worth trying – especially if we want a cleaner, fairer energy system powering our digital world.

Shareholders – companies work on behalf of shareholders to deploy fossil-free energy

Finally, the last source of money is from shareholders themselves.

Broadly speaking, the larger a company is, the more easily it can either pay for infrastructure outright from its cash reserves, or borrow money to do so.

When it comes to the internet the sums accessible for shareholders, particularly big ones can be eye popping.

In 2020, in a bid to create a homegrown cloud computing sector, the European Commission announced it would invest up to 10 billion euros over 7 years, in its digital sector.

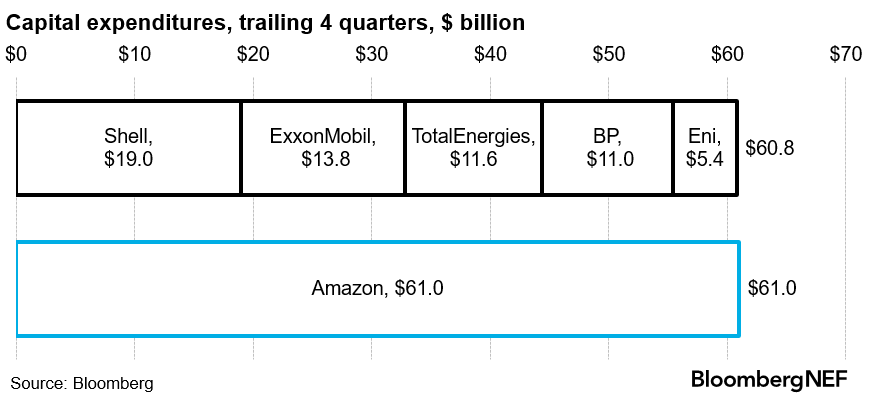

By comparison, in the last year, Amazon all by itself reported spending around 61 billion US dollars on capital expenditure. Capital expenditure is the kind of spending that includes datacentres, large renewable energy infrastructure and so on, and 40% of this 61 billion dollars is being spent on AWS.

This is more than the four largest western oil companies, Shell, ExxonMobil, Total Energies and BP combined.

Digital infrastructure, like clean energy is very capital intensive. A single, fully loaded server can cost 50-100k EUR, and once you realise that 10-20 servers might fit in a single server cabinet, it’s not hard to see how a single rack can represent a seven figure amount all by itself. Now, think how many racks you might expect to see in a big hyperscale datacentre.

Cloud computing is very profitable, and companies running datacentres don’t need to sell that much of their compute capacity to break even. This means it’s comparatively easy for them to raise more money to re-invest in digital infrastructure, which again has a pretty low break-even point, creating a flywheel effect. This is largely what we’ve seen with big cloud players do over the last 5-10 years, and once you know this, it’s easy to understand how some of this money has been used to arrange the kinds of 15 year power purchase contracts like the Google example mentioned earlier – especially now we can see how they make the economics even better for large tech companies.

So that’s shareholders as the final source of money. They’re an incredibly powerful engine for change, but it’s also important to understand how the businesses work, and where the gains are going if you want to have a sensible discussion about how we pay to get a cleaner, greener internet.

It’s also worth remembering that large companies like Amazon and Microsoft might be huge players when it comes to greening the internet, but they’re also the market leaders in enabling these same oil companies to accelerate drilling for fossil fuels. When a single oil and gas AI contract to extract for fossil fuels can have the same annual carbon footprint as a tech giant, this is worth remembering, and bearing in mind when pinning all our hopes on them to deliver a greener digital industry.

Recap

In this post we covered three main sources of money available for paying for a transition of clean energy and away from fossil fuels, and we covered examples of how they help deploy greener infrastructure.

We also touched on how there’s more to a sustainable and just internet to using efficient servers, and renewable energy – there are still issues of equity that need to be addressed, and ignoring them will likely lead to mounting opposition in the long term.

If you’d like to learn more you can fellowship posts, where we explore these themes in more detail, read Branch, the magazine we publish, or read our latest report, the Fog of Enactment. If you prefer email, you might like Greening Digital, our newsletter.